Boston Common, Boston, Massachusetts, USA

Around Late December 2024, just after Christmas, I was on vacation with my family at the New England area, and we were in Boston. We planned to explore there for a day, and we decided to book for a tour of the Freedom Trail, since a family friend had recommended to us.

We were told that this tour would get deep into American History and the start of it, and we would also see many important monuments rising up to the Revolution. So, we arrived at the Boston Commons coming off Park Street Train Station, and we tried to look for our tour guide in the crowd. Luckily, he was pretty easy to find, since he was in 18th century clothing. Now,

This, is Harbottle Dorr Jr and he is a merchant who liked to collect and read newspapers. He had a big collection of those in his shop. He is also a member of the Sons of Liberty, who were a group that opposed the British Rule in Boston. I’ll get more into them later. The reason why he’s holding a glass bottle, since the bottle helps people to remember his name as Harbottle, plus he would hold that bottle in the air to prevent from people from getting lost in the busy city of Boston.

I’ve done my best to capture and summarize the highlights based on what I learned from Harbottle Dorr, our Tour guide and my own research.

Our trip started with a grand “hurrah!”, as shown in the video. I noticed that there was short line of red brick on the pavement leading into the street. Harbottle explained that was the Freedom Trail, but Harbottle insisted that “In a very Bostonian way, we’re walking away from the Freedom Trail. You can’t tell me what to do.” (We eventually went back on the trail but it was a quick detour).

Harbottle started off with the history of the Boston Commons, and I found out that was years old.

A man named William Braxton, who was the first European to live in Boston had his farm used become a Community Common for the public, and thus how it was made. The Common served as a combination of public, military, agricultural, and recreational purposes.

Harbottle Dorr began his story with the Indigenous peoples of Boston, specifically the Pennacock and Pawtucket tribes. These tribes had lived in the Massachusett area for over 10,000 years. In the 16th century, Europeans began arriving in Boston, bringing many diseases with them on their ships.

These diseases devastated the Indigenous population in Massachusetts, wiping out 90% of their people and nearly eradicating them entirely. William Braxton played a key role in bridging the gap between the European settlers and the Indigenous peoples, fostering a period of harmony between the two groups.

The Europeans who settled the area were known as the Puritans. The Puritans were a group of English Protestants who sought to “purify” the Church of England by opposing its practices and focusing more on biblical teachings. In 1630, under the leadership of John Winthrop, they founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony, with Boston as its capital. The Puritans were also instrumental in establishing Harvard, which was originally a literacy school for Bible reading.

William Braxton, who lived in Boston, grew disenchanted with Puritan beliefs and their way of life. Dissatisfied, he sold the land of Boston to the Puritans and left to settle in Rhode Island. He became one the first European settlers in Rhode Island.

An example of the extremism of the Puritans was reflected in their laws. For committing offenses as simple as stealing or adultery, individuals could be hanged, as dictated by their strict interpretation of the Ten Commandments. Harbottle Dorr explained that the site of these executions is now located beneath a children’s playground in the Boston Common. He suggested this was likely an intentional decision to cover the dark history of the area with a cheerful and bright atmosphere.

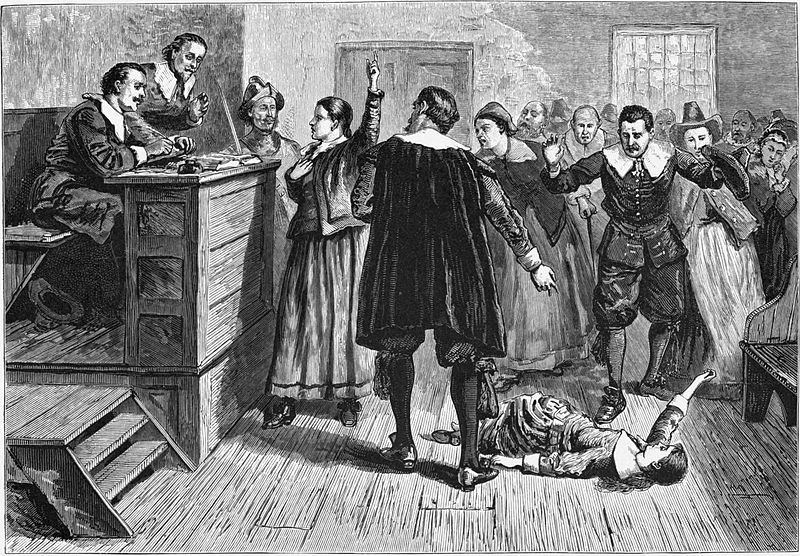

Another notable aspect of the Puritans is their role in the Salem Witch Trials. Over 200 women were accused of being witches, and many were executed at the small village of Salem, Massachusetts These events led to a significant loss of public confidence in the Puritan government, sparking movements that drew people away from Puritan congregations.

By the 18th century, New England society evolved into a more secular culture. Education, politics, and commerce began to eclipse religion as the central focus of daily life.

Another important figure to discuss is Margaret Foley. She began her career as a milliner (hatmaker), a common profession for working-class women of the time, before transitioning to a life of activism. Foley took voice lessons and became an opera singer, which gave her a loud and commanding voice that she used to great effect.

She often confronted hecklers who spoke out against women’s rights in front of the parliament building, using her powerful voice to shut them down. When the police deemed her actions a public disturbance and tried to stop her, Foley found creative ways to continue her activism. She took to shouting from rooftops, but when the authorities began cracking down on that too, she went a step further—she flew over in a hot-air balloon to make her voice heard.

Park Street Church, Boston, Massachusetts

Next, we crossed the street and arrived at the entrance of the Park Street Church. This church served as a stronghold for individuals like William Lloyd Garrison to promote religious life and social justice during the 18th century. This was particularly significant, as such topics were not commonly discussed at the time.

The Park Street Church is a historic building, having witnessed many key events during the American Revolution and over the years since.

Granary Burying Grounds

After that, we walked down the street for about a block and reached the Granary Burying Ground. It’s one of the oldest cemeteries in Boston. Upon entering, we noticed many graves that had been almost consumed by the ground, with their inscriptions faded and unreadable.

An interesting fact about the Granary Burying Ground is that everywhere you step, you’re likely walking over at least five bodies. The city of Boston would dig 20-foot-deep holes, filling them with coffins stacked one on top of another until they reached the surface, after which they would dig another hole.

This method was born out of necessity. In the 17th and 18th centuries, Boston was a small and densely populated town with limited land. Frequent outbreaks of diseases like smallpox and cholera caused many deaths, increasing the demand for burial spaces. Despite its crowded nature, the Granary Burying Ground became the final resting place for some of the most influential figures of the American Revolution.

Our first stop at the Granary Burying Ground was the gravestone of James Otis, one of the notable figures interred there. Otis was a prominent lawyer who championed colonial rights and liberty. His arguments against arbitrary government authority played a crucial role in laying the foundation for the American Revolution, influencing both the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution.

Otis is also famously associated with the phrase “no taxation without representation,” meaning that it was unconstitutional for the British Parliament to tax the colonies without their consent and that the colonies should have representation in legal and legislative matters.

An interesting detail Harbottle shared about the grave is that the gravestone of James Otis does not mark his exact burial spot. It serves more as a symbolic marker to help visitors locate his grave, as the precise location of his burial remains unknown.

Next, we visited John Hancock’s grave. Hancock was orphaned at a young age and adopted by his wealthy uncle, who owned a successful mercantile business. He became a leader of the Sons of Liberty and served as Governor of Massachusetts. Known for his charisma, wealth, and extravagant lifestyle, Hancock was famous for hosting numerous public gatherings.

He is celebrated as a symbol of American independence, not only for his iconic signature on the Declaration of Independence but also for his leadership, political savvy, and financial support during the Revolution. His blend of patriotism, boldness, and personal style made him one of the most recognizable figures of the Revolutionary era.

Like James Otis’s grave, Hancock’s actual burial site isn’t beneath the large monument. Instead, it lies beneath the pot-like structure next to it in the accompanying photograph.

Harbottle also mentioned a grave near Hancock’s, engraved with: “Frank, Servant to John Hancock.” There are no records detailing who Frank was, beyond the likelihood that he was enslaved to Hancock. The mystery lies in the fact that references to Hancock’s other servants have largely faded from history, yet Frank’s inscription remains clearly visible. This has led historians to suspect that Frank held special significance to Hancock, though the exact reasons remain unclear.

We then visited Paul Revere’s grave. Paul Revere was a silversmith and military official born in Boston. He was a highly skilled artisan—if it ended with “-smith,” he could likely do it. His work spanned silverware, copperplate engravings, and even early industrial manufacturing. Revere was also a member of the Sons of Liberty and participated in acts of resistance, including the Boston Tea Party.

He is best known for riding from Boston to Lexington to warn Samuel Adams and John Hancock of approaching British troops. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem, “Paul Revere’s Midnight Ride,” immortalized this event, but it also exaggerated certain details. As Harbottle explained, the true story of that night differs from the popular legend—and it’s even more fascinating.

The British in Boston were ordered to march on Concord to seize colonial weapons and arrest Samuel Adams and John Hancock, believed to be in Lexington. A colonial intelligence network, including Paul Revere, spotted the British crossing the Charles River, so two lanterns were lit at the Old North Church, signaling the troops were moving “by sea.” Revere rode to Lexington, warning local officials along the way by knocking on doors. William Dawes had a similar mission, and together they decided to continue on to Concord. They picked up Samuel Prescott en route—he had just fled his girlfriend’s house to avoid her angry father.

British patrols intercepted the three riders. Prescott managed to escape into the woods, Dawes fled successfully, but Revere was briefly captured. He misled the British about the militia’s strength and was soon released—without his horse. Thanks to the warnings spread by Revere, Dawes, Prescott, and others, militias were ready to confront the British the next morning, marking the first skirmishes of the American Revolution. As Harbottle noted, the phrase “The British are coming” is likely a myth, but what is most likely what he shouted was “The Regulars are Coming Out!”.

This the account that Harbottle had told us, but there are many accounts that people will tell you about Paul Revere’s midnight ride.

After visiting Paul Revere’s grave, we stopped by Samuel Adams’s grave, where Harbottle shared more about Adams’s background and significance. Along with John Hancock, Samuel Adams founded the Sons of Liberty. He had a remarkable ability to inspire and organize resistance, playing a critical role in uniting the colonies and securing American independence. Known for his organizational skills and use of speeches, pamphlets, and newspapers, Adams effectively rallied public opinion against British rule.

He was also a key figure in the Boston Tea Party. When a British trade ship arrived carrying a large quantity of tea, a crowd gathered to decide its fate. Samuel Adams joined the crowd and said, “Gentlemen, this meeting is adjourned.” This statement served as a signal, prompting them to discard the tea into the harbor.

After discussing Samuel Adams, Harbottle pointed out the Beantown Pub across the street—one of his favorite bars, though lacking in historical significance.

He joked that it’s “the only place in Boston where you can drink a cold Sam Adams while looking at a cold Sam Adams,” referring to both the beer and the grave across from it.

Interestingly, while Samuel Adams was indeed a brewer, he had no direct connection to the modern Sam Adams beer company, founded by his great-great-grandson. That ancestor used Adams’s recipe for inspiration and named the brand in his honor.

Lastly, the face on the Sam Adams beer label isn’t actually Samuel Adams. Since he was considered rather unappealing in appearance, the brewery opted for a more flattering figure—one that actually resembles Paul Revere.

As we were leaving the graveyard, I noticed a large stone monument in the center engraved with “Franklin.” Naturally, I assumed it belonged to Benjamin Franklin—he was the first name that came to mind. I was quickly corrected, though, since Benjamin Franklin was from Philadelphia and had no direct connection to Boston, so he wouldn’t be buried there.

When I asked Harbottle Dorr about it, he explained that the monument actually marks the burial site of Benjamin Franklin’s parents, who were from Boston. Apparently, in the 1800s, the city believed that if people saw a large monument engraved “Franklin,” they would assume it was Benjamin Franklin’s grave. By the time visitors realized the truth, the city would have already profited from their visit.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.